1929

The Lateran Treaty

The Lateran Treaty between the Italian State and the Holy See on 11 February 1929 coincided with the tenure of the guard commander Hirschbühl. In it, the Holy See had been granted the exclusive and absolute right to manage all its political and legal affairs on its own. The Swiss Federal Council confirmed the parliament's opinion on 15 February: "The papal guard cannot be regarded as foreign, armed unit in accordance with Article 94 of the military criminal law, because this force is a simple security police, and anyone can, as before, come into their service, without the consent of the entire Federal Council."

The creation of the new state, the Vatican City, required on its border the introduction of regular checkpoints at the Arco delle Campane (Bell’s Gate) and the Porta Sant'Anna (Saint Anna’s Gate). The Portone Borgia, however, was closed. In 1929, work began on the construction of new office and living quarters for officers and NCOs. It remains to be said that, besides the already mentioned works, the restoration of the little church consecrated to St. Martin and St. Sebastian, which is situated in the Swiss quarters, was also restored. Pope Pius V had built this church in 1568 specifically for the Guard, which now was once again at the disposal of the Guard. The church of San Pellegrino with its century-long history of the Swiss with the Holy See, on the other hand, was made available to the Vatican’s Vigilanza.

1870

End of Papal State

The outbreak of war between France and Prussia in July 1870 marked the end of the secular power of the Church, as the French occupation troops led by Napoleon III had to move back to their homeland. The Italian government assured the Pope compliance with the agreement of September 1864, allowed, however, when the fortunes of war turned for Napoleon III, to besiege the regions belonging to the church by the army of the Kingdom of Italy.

After the defeat at Sedan and the proclamation of the French Republic, the military siege was intensified, and on the 20th September 1870 the royal troops stormed, after a brief gun fire, the «Porta Pia» and marched into Rome. Pius IX wanted to avoid bloodshed and ordered the commander of the Papal forces, General Chancellor, to limit the defence to an absolute minimum to prove that one would only avoid brute force. On the following day the papal troops were dismissed, and only the Swiss Guard remained in the Vatican.

Thus ended a centuries-long period, in which an army under the leadership of the Pope was required to secure the secular power of the church. From then on, the Swiss Guards’ only duty was to protect the life of the Pope and to ensure the safety of the Vatican and the Pope's summer residence in Castel Gandolfo. Therefore, Stalin’s question about how many divisions the Vatican required, made no longer any sense. It shows a too «realistic» and short-sighted view of the facts that determined the course of history.

1527

Sack of Rome «Sacco di Roma»

On the morning of 6 May 1527, from his headquarters, the monastery of S. Onofrio on the Gianicolo, Captain-General of Bourbon gave the signal to attack. Near the «Porta del Torrione» he was mortally wounded, as he prepared to storm the ramparts. After some hesitation, Spanish mercenaries broke through the «Porta del Torrione», while the soldiers invaded the «Borgo Santo Spirito» and the «Borgo San Pietro». The Pontifical Swiss Guard which had assembled near the obelisk, which then stood near the «Campo Santo Teutonico», and the few Roman troops fought a futile battle. The commander Kaspar Röist was wounded and later brutally massacred in the quarters by the Spaniards, right before the eyes of his wife, Elizabeth Klingler. Of the total of 189 Swiss Guards only 42 survived, who, under the command of Hercules Göldli, accompanied Clement VII to his retreat, Castel Sant'Angelo.

The others fell heroically before the high altar of St. Peter, along with 200 others who had fled into the church. The rescue of Clement VII and his people was made possible through a secret escape passage, the so-called «Passetto», which Alexander VI had created on the wall that leads from the Vatican to Castel Sant'Angelo. The savage horde was in a hurry, because it feared that its retreat would be cut off by the League. Soldiers and Spaniards poured over the «Ponte Sisto» and into the city for eight days, spreading terror and violence, looting, murdering and transgressing. They even broke the tombs of the Popes, including the one of Julius II. The death toll is estimated at 12,000 and the bounty amounted to ten million ducats.

All that happened is not surprising when one considers that the imperial army, and even more so the Frundsberg’s soldiers, were led by the idea of a violent crusade against the Pope. In front of Castel Sant'Angelo and witnessed by the Pope himself, a parody of a religious procession was staged, calling on Clement to hand over to Luther the sails and the oars of the «Navicella» the so-called Peter’s boat. The soldiers chanted: «Long live Luther pontifex». In derision, Luther's name was carved into the fresco «La Disputa Santissimo Sacramento» (The Disputation over the Most Holy Sacrament) by the sword point in the Stanzas of Raphael, and another inscription glorified Charles V. Kurz, which is expressed in the judgement of the Prior of the Canons of St. Augustine: «Malifuere Germani, pejores Itali, Hispani vero pessimi.» (The Germans were bad, the Italians worse, but worst of all were the Spaniards.)

Apart from the irreparable loss by the destruction of the relics during the «Sack of Rome», an inestimable amount of pieces of art were also lost, like most of the churches’ precious metal works. On 5 June, Clement VII surrendered and had to submit himself to hard terms: the surrender of the fortresses of Ostia, Civitavecchia, and Civita Castellana, the abandonment of the cities of Modena, Parma and Piacenza and the payment of 400,000 ducats. The papal garrison was replaced by four companies of German and Spanish soldiers. The Swiss Guard was abolished and its service taken over by 200 mercenaries. The Pope asserted that the Swiss survivors were allowed to enter the new guard, but only twelve of them took advantage of this offer. Amongst them were Hans Gutenberg of Chur and Albert Rosin of Zurich. The others did not want to have anything to do with the hated mercenaries.

1512

Swiss mercenaries

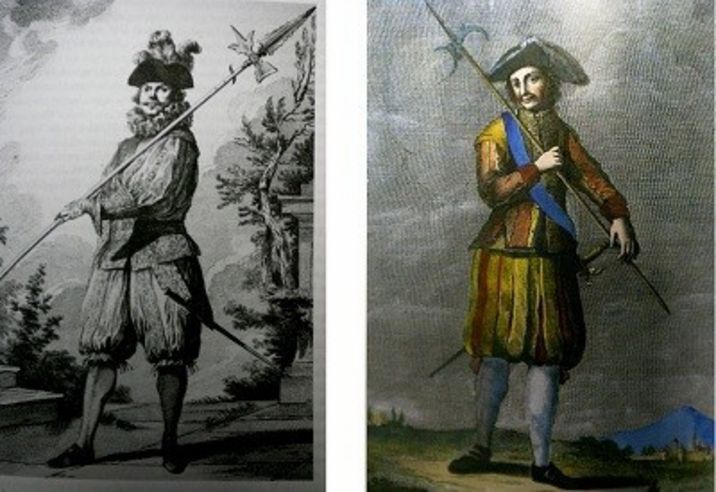

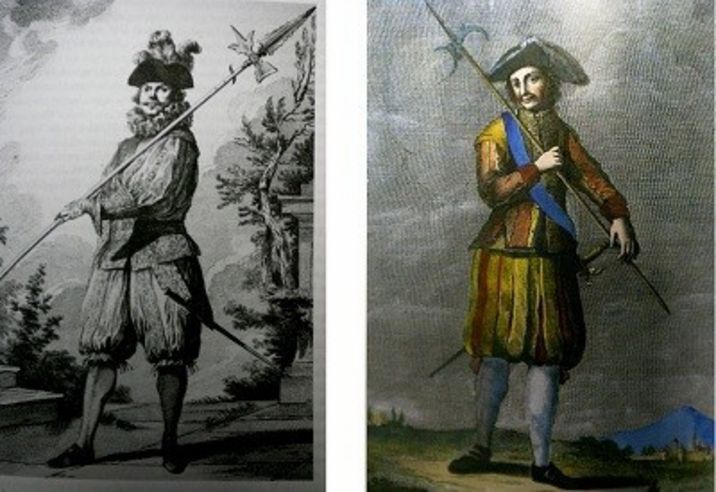

The Pope’s choice to hire Swiss mercenaries was no accident. The Swiss soldiers had a reputation of being invincible thanks to their courage, their noble intentions and their proverbial loyalty. The great Roman historian Tacitus noted many centuries ago: «The Helvetians are a nation of men of war and its soldiers are well known for their fighting qualities.» For this reason, the Swiss cantons, who allied themselves with one country and then again with another, played a significant role in European politics. In 1512 they decided as an ally of Julius II, the fate of Italy, and the Pope honoured them with the title «The guardians of the freedom of the Church». At that time, when mercenaries were common, a highly defensive people lived in the Central Alps. The first Swiss cantons were overpopulated with their approximately 500,000 inhabitants. Due to the difficult economic situation at that time, there was great poverty. The only way out of this situation was emigration and the most lucrative work was the mercenary service.

15,000 men were available for this service, organised and controlled by the small federation of cantons . This federation regulated the recruitment of men of war, and received wheat, salt or favourable trading conditions in return. The Swiss regarded the mercenary service as a temporary one, lasting only during the summer months and, therefore, only participated in brief major campaigns. They then returned home and lived off their pay and loot through the winter. They were the best soldiers of their time, who had invented a clever tactical fast-striking movement strategy without cavalry and only little artillery that was superior to all others. Therefore, they were hired by both France and Spain. They formed an impenetrable semi-flexible wall, studded with iron. It is almost impossible to understand the wars in Italy, without taking these mercenaries into account. Already in the 13th and 14th century, after the Swiss independence, many soldiers did military service in Germany and Italy, and because the cantons could not prevent this type of emigration, they tried to at least keep it under control.

1506

Foundation

For over 500 years, the Swiss Guard has been at the service of the Popes and has been watching over the Vatican. It all began in 1506 when the first Swiss arrived on request of the then Pope Julius II. The official day of the foundation of the Pontifical Swiss Guard is the 22 January 1506, the day when 150 Swiss, led by their Captain Kaspar of Silenen in the Canton of Uri, entered the Vatican for the first time through the «Porta del Popolo» and were blessed by Pope Julius II.